The family had been living in the Grayson area for several years and, in September 1935, Elmer paid Otis L. Gunter $370 for 37 acres of land in Snellville bordered by Springdale and Greenvalley Roads. Timber was cut from the property and taken to a sawmill for constructing of the house.

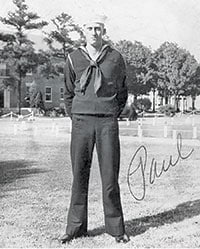

Subsistence farming was quite common in this area, and all family members were needed for cultivation and harvests. Like many young men of that era, and rural location, Paul lived with his parents and worked on the family farm. However, life wasn’t very exciting on the farm so, in February 1938, Paul chose to seek a more interesting life by joining the U. S. Navy.

After three months of training in Norfolk, Virginia, he was assigned to the USS Boise, a Light Cruiser, to go on a shakedown cruise (a nautical term in which the performance of a ship is tested before it enters service or after major changes) to Monrovia, Liberia and Cape Town, South Africa. Until November 1941, she operated alternately off the U. S. west coast and in Hawaiian waters.

On one cruise to Hawaii, Paul was the Oil King, assigned to manage the pumping of oil into the boilers. A mistake that Paul made in closing one of the valves caused the ship to lose power. However, as everyone scrambled around to determine what had happened, Paul discovered the reason and, instead of being disciplined, was recognized for discovering a valve control procedure that was not in the operations manual.

It was while the Boise was in Hawaii that Paul went aboard the USS Houston, a Heavy Cruiser, and decided that he wanted to transfer to that ship because it was scheduled to sail to the Asiatic Station. Although Paul’s orders to transfer to the Houston were approved, his Commander tried to talk him out of it because he didn’t think it was going to be the adventure that Paul had imagined. It turned out to be quite an adventure and one that proved the Commander was correct.

In the fall of 1940, the Houston arrived in the Philippine Islands and was based in Manila. After Pearl Harbor was attacked on December 1941, the Houston sailed to Darwin, Australia, where she arrived on December 28. The Houston left Darwin on February 15, as part of the American-British- Dutch-Australian naval force to escort troop convoys, supply ships and tankers. During one Japanese air attack, Houston distinguished herself by shooting down 7 of the 44 planes that attacked.

After another engagement with the Japanese Navy at the Battle of the Java Sea, the Houston and a sister ship, the Perth, sailed to Jakarta where they attempted to resupply but were met with fuel shortages and no available ammunition. On the way back to Australia they encountered more enemy warships. On March 1, 1942, the Houston was struck by four torpedoes and, a few minutes later, rolled over and sank.

Of the 1,061 men aboard 368 survived, only to be captured by the Japanese and interned in prison camps. Houston’s fate was not fully known by the world for almost nine months, and the full story of her last battle was not told until the survivors were liberated from prison camps at the end of the war.

The following is an edited transcript of Paul’s description of the events surrounding his escape from two sinking ships, within a 24-hour period, his capture by a Japanese warship and liberation from the prison camp and return to Snellville.

We were hit with torpedoes, our engines were knocked out, and one of the oil tanks was afire. So we got orders, around twelve o’clock, to abandon ship.

I was Water Tender down in number one fire room. It looked like the whole ship was on fire and like it was the end. In a few minutes, we had to go up the hatch where we had planned a secondary way to get out of there, which came in very handy at the moment. There was only one hatch to exit the fire room with sixteen dogs to secure it. The under side the dogs had only a little knuckle, like the end of your thumb, but a sailor on the top was supposed to loosen the dogs by the handles and let us out.

We kept a ball-peen hammer up in the hatch so we could hit those dog knuckles from the bottom and release the hatch in case of an emergency. We hit the dogs with the hammer, and they all flew open, and we got out. There was a fire in the passageway, but we ran through it to another door where we ran through more fire to one of the main decks.

When we got up on deck, we found that the man that was supposed to let us out of that hatch, was a Warrant Officer that had abandoned ship with his pistol and life jacket leaving us in the fire room to get out the best way we could.

While standing on the port side of the ship, a shell hit one of our pom-pom guns and exploded. It threw me into the air outside of the lifeline swinging against the side of the ship with my right foot caught in the lifeline. Two Water Tenders, standing beside the lifeline, reached out and grabbed me by the hand and pulled me back in and said, “Come in here boy, where are you going?” Neither of them survived.

A Seaman and I ran up to the locker and got two life jackets. We were the only two left on the front of the ship, but the Bo’sun’s whistle signaled for everybody to go to the back of the ship.

Hearing the screams of men moving in that direction, I realized that they were passing through an area that was still being shelled by enemy ships. So I went over on the starboard side of the ship and just walked off… it was already leaning so much that I didn’t have to jump off, just walked into the water. But I didn’t realize, at that time, that the ship was still moving pretty fast because it didn’t have any power, so they had no way of stopping it. As I got out into the water I felt hot steam hit me in the belly, but it passed on by me in a few seconds, and I was left swimming away from the ship.

I could see a little of the land in the distance, like a quarter moon shining, a little of a mountaintop sticking out about 8-10 miles out from where our ship sank. And that mountaintop was what we had to swim toward. I swam on a little way, and I ran into a Seaman who grabbed me around the neck from the back and kept holding on to me. He said he didn’t have a life jacket and couldn’t swim. So I told him to hold to my leg, and I would swim. And he said, “No.” He was going to hold onto me and wasn’t going to turn me loose.

And a little later a buddy of his swam by, and he left me and went over and took hold of him the same way. But, they never made it because he wouldn’t hold on in a way that would let the other man swim.

I was then on my own for a while and soon ran up on a sailor. We agreed to try to stay together. A while later he said, “Duck. Swim underwater, dog paddle and swim underwater. They’re shooting at us in the water.” I ducked underwater when a searchlight passed overhead, and when I came back up I couldn’t find the man although I called and searched for him for quite a while. He was a good swimmer so he must have been shot.

Many times I would swallow saltwater, vomit it up and keep going. I always thought that I could make it to the island.

I never saw a raft or anyone else until the next morning when, swimming by myself, I saw some ships pass me going toward land. When it became light, I could hear Japanese sailors on the beach unloading cargo. So I decided to turn around and swim back toward Sumatra, about 20 miles on the other side of the strait.

One of the ships that had passed me was a Japanese Tanker, and they had sent out a small boat to capture us. There were already eleven other American prisoners in the boat, but I had never been instructed on what to do in a situation like that. I kept swimming away from them, and they kept hollering at me and motioning for me to get in the boat, but I kept swimming away. After a while, one of the men came close to me and raised an oar like he was going to hit me with it. So I grabbed onto the boat and, after nine hours of swimming, they pulled me into the boat. In the water, I felt like I could swim the 20 miles to Sumatra, but once in the boat, I was so tired I could hardly move.

We were taken to the Tanker that was staffed by Merchant Seamen, not sailors and soldiers. A Japanese officer that had been to school in the United States, talked with us and got our names and those of our ships. He continued to interrogate me and asked how many submarines we had in that area. I told him that I did not know, but I thought that we had a good many. When he first came out to talk to us, he had taken my wallet and took it inside the ship. He later returned it with all of the $643 and 7 Dutch guilders that had been in it.

We were really tired and sleepy, so I fell down on the deck and went to sleep. A few hours later a sudden jolt, the mast shaking and chains rattling awakened us. The Seamen were running around, shouting and firing their guns. When we looked over the side, we saw an Allied submarine submerging. It had fired a torpedo into our Tanker and into another that had been beside us.

We thought of abandoning the Tanker and swimming to the beach to escape, but there was so much oil flowing from the tankers that it would be impossible to swim. As the front of the Tanker was already sinking, a Japanese Destroyer came to the back of the ship and took us and the crew- members off, and we were, for the next 31⁄2 years, prisoners of war to the Japanese Navy.

Two days later over 300 Americans, Australians and Indians were offloaded on Java and marched for about 36 hours to an old movie theater building where they were held under crowded, miserable conditions for about 6 weeks. They were given very little water and food with only a large outside pit for a latrine and no way to bathe or even wash their hands. Before being marched to Batavia, they were taken to a river where they could bathe and wash their clothes.

Batavia was a large, old camp of the Dutch army where they found other prisoners, including a lot of Dutch. The conditions were better with more space, running water and bunk beds with grass mats filled with bed bugs and roaches.

We would try to go out on working parties because we could sometimes find some food to eat or other things that would make our lives more convenient. We also traded items with other prisoners. However, it seemed that the guards looked for any reason to beat us with bamboo poles, did so when catching us.

We were later taken to a camp in Singapore for three weeks and then on to a camp in the mountains at Ohashi, Japan. There we worked in a mine and then at a foundry. The winters were very cold in that area with a lot of snow. We didn’t have adequate clothes for the weather and suffered a lot with it.

When the camp Commandant and guards realized that Japan was losing the war with the United States, they became less brutal and more accommodating to the prisoners. We noticed that some guards abandoned their watch and left the camp. One day a Jeep with five Americans came into the camp and told us to continue living in the camp and to wait for a call from Tokyo for orders on evacuation. A B-29 flew over, dropped a field radio with instructions to mark an area where food would be dropped to us… parachutes dropped with steel drums full of canned good, cigarettes, candy, etc.

After a couple of weeks, we were taken by train, down the mountain, to a temporary airbase and boarded planes that took us to Tokyo. We were given medical attention and good food and then put on a ship to Guam where we spent a couple of days in a hospital. From there we went on to Hawaii where we were given new clothes and then flew to Oakland, California.

Snellville didn’t have telephones when I left there in 1938, so I called my brother Boyd, in Virginia, and talked with him. In a few days, I was able to catch a military flight to Independence, Missouri and a train to Atlanta and a bus to Snellville. It was about 2:00 AM when, after a couple of attempts to wake my sister, Vera, I finally got someone to answer the door. Vera almost fainted because they had received no notification that I was still alive. About daylight, W. C. Britt drove me down to my parents’ home.

Paul Gilleland was a farmer who, with his military back pay, bought land near his parents’ and spent most of the rest of his life farming. He married Willa Nell West in 1946, and they had two daughters, Paula Nell (Brooks) and Hannah Ruth (Mitchell) and a son (Harold Edwin). He married Mary Lounette Nors- worthy in 1970. Paul died in 2001 and a section of Highway 78, going through Snellville, was dedicated to him.

After the rigors of farming began to take its toll, he drove a school bus for a while and worked as a custodian in one of the local schools. Below is a comment from a student that knew Paul.

A letter from Steve Burns of Marietta

“I was reading the obituaries recently about the incredible life of Paul Gilleland. I can’t recall the name of any one of my elementary school teachers, but I vividly remember Gilleland. Every day for six years I would pass him in the halls as he went about his duties as custodian.

Unfortunately, I never knew of the hardships that he endured as a POW survivor of WWII until after his death. Gilleland is one of the millions of Americans who are our true heroes who sacrificed for freedom without fanfare, chest thumping or the need of a microphone and camera.

Thanks to Gilleland, I’ll think twice the next me I look indifferently at a man holding a mop.“

{field 2}

{field 3}