Attorney David Hudson says elected officials do not give up their First Amendment rights to free speech simply because they hold office or because they participate in an executive session of a governing body.

Hudson told members of the Georgia Press Association earlier this year: “From time to time, elected officials such as city council members, county commissioners, school board members or appointed members of the board of government authorities will receive advice (usually from a lawyer representing the public entity) that the public official may not disclose information learned in a closed session. Such advice has no basis in fact or in law.”

Hudson adds: “Elected officials are subject only to the voters.”

He explains there is an obvious misunderstanding of the Code of Ethics contained in O.C.G.A 45-10-3 that prohibits them from disclosing proprietary information for “personal gain” or in violation of the public trust. He says: “None of its provisions would prohibit an elected or appointed member from disclosing what occurred in an executive session if the member felt it was in the public interest to do so.”

In fact, Hudson feels that the state’s Constitution might even compel an elected official to disclose what occurred in a closed-door executive session.

In the same article he commented on Article I, Sec. II, Paragraph I of the Georgia Constitution. “It states: ‘Public officers are trustees and servants of the people and are at all times amenable to them.’ Thus if the public officer learns of something that occurs in a closed session that he or she believes should be known by the people to whom the public officer is a servant, there is no prohibition in Georgia law that would prevent such disclosure or subject the public officer to any measure of discipline.”

Hudson says that disclosing information from executive sessions might anger fellow officials, but in his opinion a public servant should weigh the public trust against the risk of creating ill-will with other members of the same elected body.

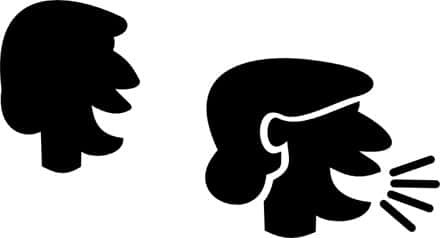

Local elected officials in county and city governments have told reporters and editors they are legally prohibited to disclose what is discussed in executive sessions.

Hudson disagrees.

In addition, Hudson has consistently opined that there are no requirements in state law to hold executive sessions for any reason. Rather, he has said, it is permitted or allowed for property acquisition, pending or actual litigation and certain personnel issues.

Jim Zachary, editor of the Henry Daily Herald and Clayton News Daily, and director of the recently-launched Transparency Project of Georgia, says: “There is a significant difference between being legally permitted to do something and being required. Every single time elected officials retreat to executive session, it is a choice they are making to conceal the public’s business. It is important they know that if even just one of them chooses to disclose what was talked about behind closed doors, they can do so without fear of violating any state law.”

Zachary continues: “These are extremely important legal perspectives. Citizens should continue to put pressure on local officials to stop doing public business in private.”

As previously printed in GwinnettForum.