Topics included defensive tactics, such as TASER and handcuffing; criminal investigations; special response team operations; basic criminal procedure, patrol and traffic operations, a criminal justice overview, city information, and a recap of changes that were made in police procedure during the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, the participants were taught by safety officers to fire a police handgun at the shooting range in Lilburn and took part in the use of a video force simulator employed in the training of police officers. A scheduled tour of the Gwinnett County jail was canceled due to the virus.

Worley said the first set of operational changes came on March 12, right around the time that classes had to be stopped. “All of the department’s public meetings were suspended, including the Citizens Police Academy,” Worley said, adding that all outside training also was canceled.

The new Lilburn Police Department headquarters building located at 4600 Lawrenceville Highway had to temporarily be closed, hardly before it had a chance to open, as patrol officers were in service from their homes. “The command staff reported on an individual and rotating basis and teleworked from their homes,” Worley said.

All these changes were in line with Gwinnett County government’s “Stay at Home” order on March 26, and a similar statewide order from Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp on April 3.

“It’s been a bit of a challenge to see how this would work,” he said.

Along with police changes, the city hall, municipal court and library branch were closed for several weeks.

Officers were cautioned as to their interaction with the public because of the virus.

Other changes, according to Worley: patrol officers went into service from their home, rather than from police headquarters, and it was permissible to handle calls over the telephone. In arrest situations, suspects were transported straight to Gwinnett County jail rather than city headquarters. Conference calls and Zoom meetings became the norm between command staff and the Criminal Investigation Division.

Worley wrapped up his session by saying that things went very well during the three-month COVID-19 time period. “Lilburn is a very special place to work,” he said.

Hedley continued the discussion with an overview of the criminal justice system and the makeup of the Lilburn force: 32 sworn officers, five investigators, two part-time officers, and five full-time civilian staff members. Other facts he shared: there were 34,637 calls dispatched last year with an average response time of three minutes for emergency calls. On an average week, Tuesday was shown to be the day when most dispatches are made.

Crimes investigated are murder, rape, aggravated assault, robbery, arson, burglary, larceny, theft, motor vehicle theft, prostitution, and pornography, among others.

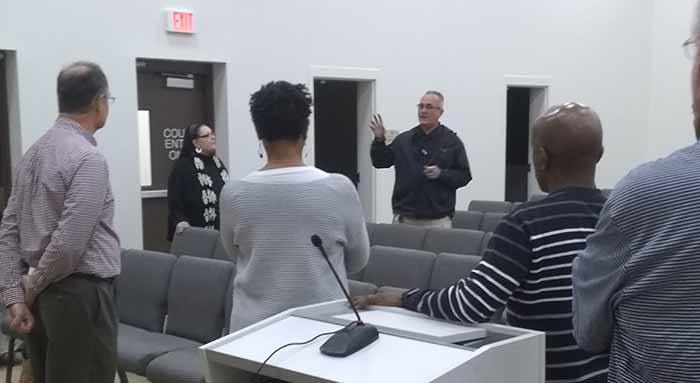

Later in the sessions, Hedley took the group on a tour of the new police facility, which includes administrative offices, records room, evidence lockers and garage, a holding cell, and the municipal court. Worley showed the roll call room where the officers congregate every morning like the same scene in the TV show Hill Street Blues.

Code of Conduct, criminal investigations, and arrest procedures were topics of discussion from Capt. Scott Bennett, who outlined the Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution which gives citizens the right against unreasonable search and seizures. “In the overview of criminal procedure, our investigative process is to make sure that reasonable criminal intent takes place,” he said. The first step in a criminal investigation is to obtain a proper search warrant (a signed piece of paper) issued by a judge to search a person, location or vehicle for evidence of a crime.

Instances in which it’s not necessary to get a search warrant include valid consent, hot pursuit, border searches, a valid stop and frisk incident, crime in plain sight, and incident to a lawful arrest. Probable cause for an arrest, he said, is “less than certainty, but more than mere suspicion.” And a person can be frisked for a weapon, but not for drugs. Bennett said that officers must avoid “fruit of the poisonous tree”, which is illegally obtained evidence.

Students learned that law enforcement agencies in the U.S. work together to solve criminal cases. Lilburn Police works with Gwinnett County Sheriff’s Office and Police Department, along with other municipal departments in Gwinnett County and elsewhere. Other cooperating agencies include the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, the Georgia State Patrol, Wildlife Resources Division, Postal Inspection, Federal Bureau of Investigation, among others.

Lt. Chris Dusick and Senior Police Officer (SPO) Mike Johnson showed the class some of the equipment used by this special team: gas masks, body armor, ladders, weapons, and tactical shields.

Defensive tactics, including the use of taser guns and handcuffing, were demonstrated by Sgt. Rob Kirschner, who told the audience that an officer’s best bet is to gain voluntary compliance from the suspect without using force. “We can’t be behind the 8-ball…if I’m going to make the arrest, it’s on me to see how much force I’m going to use,” he said. “If we can’t control the situation, we’re in trouble and we can get killed.”

To gain compliance of a suspect, OC (Oleoresin Capsicum) or pepper spray is a “less than lethal” force to gain compliance while the perpetrator is blinded by the spray. It contains cayenne pepper and is the successor to the old “night stick” or baton previously carried by officers in years past. However, the latest modern version of a telescoping baton used by officers is strong enough to break a bone.

The taser is a less lethal use of force option, a great tool, Kirschner said, but one “where taser cartridges are not going to work all the time.” Shotguns loaded with pellets might be used in a standoff situation when a suspect is barricaded inside a defensive position.

Patrol and traffic enforcement were topics discussed by certified instructor SPO Matthew Legerme, who said officers are trained in the proper technique to make a traffic stop, as the department of traffic enforcement issues citations and written warnings.

The most common traffic violations, according to Legerme, are speeding (1,500 violations last year), driving under the influence (DUI), distracted driving (texting or looking at your phone), and seat belt violations.

To help reduce personal injuries and fatalities, police officers work to educate the public–for example, to make sure that children are properly positioned in the right kind of car seat. Data on violations are collected and analyzed by the proper officials to determine strategy.

In addition, Lt. Allen told the group that fines garnered from speeding are not used by the police department. “It’s against the law,” he said.

Gwinnett County District Attorney Danny Porter, D.A. since 1990, discussed Georgia criminal law. Porter said with the population of the county increasing to one million, so has crime risen seven percent in the past 10 years. In 1981, only 108,000 residents lived in the county. “I work for you,” Porter told the class, “and I have a reputation for being a hard-nosed prosecutor.” He has 146 employees in his department who work with 11 superior court judges.

Cases such as armed robbery, murder, involuntary manslaughter, kidnapping, and rape are presented to the grand jury, 23 citizens chosen at random.

City Manager Bill Johnsa, in his post for 12 years, and Jenny Simpkins, assistant city manager, told the class about how the city operates. Johnsa said city and counties are different because a county has constitutional officers, while cities don’t; and that counties are created by the state legislature, while cities are formed by charter. County commissioners represent districts, while city council members are elected to at-large posts. Johnsa said priorities in the city include public safety; economic development; and responsible, transparent government.

According to Johnsa, the city has won awards from various websites and publications for being one of the best places in the Atlanta metro area and Georgia to live.

Class members were able to test the use of force simulator that officers use in their training by standing before a video screen holding a laser pistol and reacting to what the suspect is doing on the screen. Following the sessions, Lt. Allen discussed what was done right and wrong in the test.

Attendees met at Main Street Gun Range so officers could demonstrate the correct way to hold a 9 mm pistol and practice shooting at paper targets. Lts. Allen and Dusik were the safety officers who instructed class members in the controlled area.

The last class was the graduation ceremony, and Chief Hedley thanked everyone for their participation, presenting each member with a Certificate of Achievement and a Lilburn Police Department coin medallion.