• What is fentanyl? Where did it come from?

• If Fentanyl is so dangerous, why do people use it?

• What’s happening is terrifying

• Opioid settlement funding to local communities presents opportunities to address this epidemic

• Gwinnett community viewpoints

• Is there any hope?

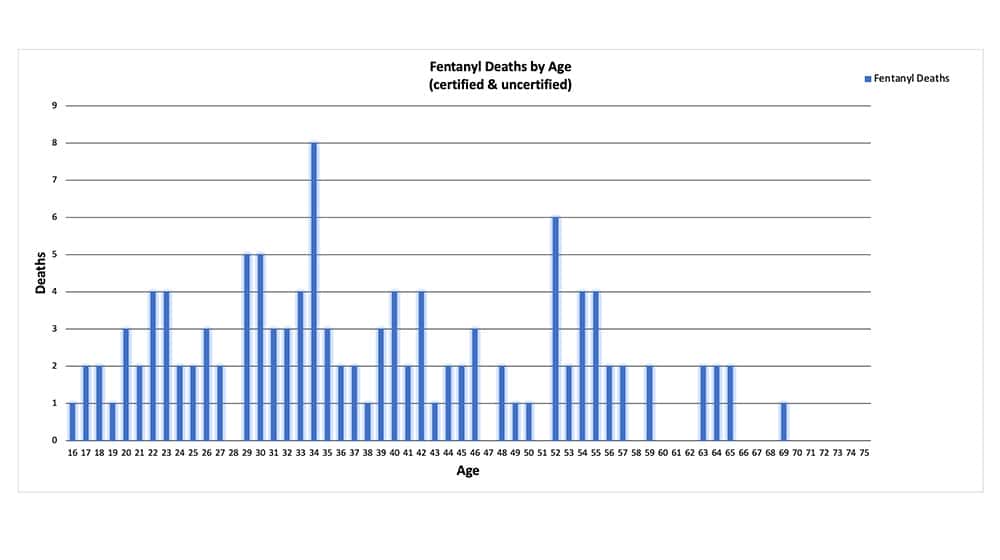

In 2022, 120 such deaths have been predicted in Gwinnett. As of the beginning of November, there were already 115 fentanyl-related deaths on record in the county, and the holidays still lie ahead. Overdoses and typically spike during the months of November and December. There has also been about a two-month delay in the Medical Examiner’s office’s ability to definitively classify a death as being fentanyl-related, because of a gap in grant funding that helps pay for this specialized testing.

“Seeing these numbers was like being in the crow’s nest on the Titanic, and looking down at something we didn’t understand, but that we knew was huge.” Dr. Terry shared. “We had a high-level view of what was happening, but we were only seeing the small tip of a very big iceberg.” The doctor said then, eight years ago, she knew that she was looking at a game-changer in the world of illicit drug use, the crippling opioid crisis, and substance abuse-related death.

What is fentanyl? Where did it come from?

Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid, a central nervous system depressant, that was created and prescribed to manage pain in very ill cancer patients. It is also prescribed to surgery patients to manage severe pain. Fentanyl patches and lollipops have been routinely prescribed to patients in end-of-life care, their value immeasurable to a patient who is suffering great pain. “In that context, fentanyl is a good drug,” Dr. Terry said. “In the hands of the wrong people, it is a very, very bad drug.”

Fentanyl has been referred to as heroin’s synthetic cousin. It is estimated to be about 100 times more powerful than morphine. It is much less expensive than heroin, and it doesn’t require expansive fields of poppy plants to manufacture. It is more addictive than heroin, because it is so very powerful. In other words, it is a drug cartel’s dream come true. It is an opioid user’s dream come true, except in this case, the dream has quickly turned into a public health crisis and a humanitarian nightmare.

Illicit manufacturers in China have begun supplying fentanyl to cartels in Mexico. Both countries now smuggle the drug into the United States, and no doubt illicit fentanyl is being cooked up in backyard labs right here at home.

If fentanyl is so dangerous, why do people use it?

Opioids are painkillers, drugs that mimic the effect of derivatives of the poppy plant on the human brain. In other words, opioids (namely, heroin) provide a powerful high, one that has been described as euphoria, a “rush,” and a false sense of escape. Users try heroin because of curiosity, because of a need for a stronger high, because of unresolved trauma, or for one of many reasons. But even with heroin, more is always necessary to achieve that elusive high.

Often, the desire to avoid the horrible effects of withdrawal drive a user to seek the next dose. No matter the reasons a person starts using the drug, it is very difficult to stop using it.

Prescription opioids came on the scene in the United States with a vengeance in the 1990s, with pharmaceutical companies downplaying the addictive properties of these “miracle drugs.” Common types of these opioids are oxycodone, hydrocodone, morphine, and methadone. But when the DEA began to crack down on the over-prescribing and misuse of prescription opioids, heroin emerged as the cheaper, more powerful, more attainable high. Heroin overdoses have skyrocketed since people, desperate for relief of anxiety, withdrawal, pain, trauma, and for an escape from reality, have turned to heroin.

Fentanyl is less expensive than heroin and much more addictive. A relative newcomer to the already devastating, widespread opioid crisis, fentanyl deaths are on the rise, and those closest to the stark reality and ultimate fallout of this phenomenon – the Medical Examiners and that office’s investigators – do not see an end in sight.

“We will never win the war on drugs,” said Chad Johnson, a Medical Examiner’s Investigator in Gwinnett County. “You will never stop people from using their drugs. Only they will stop using their drug of choice, and only when they decide, and only with a lot of support.”

“The best we can do is educate the public about what’s going on,” said the Medical Examiner Chief Investigator, Eddie Reeves. “People do not know that this is happening all around them.”

Fentanyl is being added to heroin to increase profits. Too, anyone can buy a pill press online, press fentanyl powder and other substances into it, and turn out a pill that looks exactly like pharmaceutical Xanax, Oxycontin, Percoset, Adderal or any drug that users seek from illicit channels. Young adults – primarily ages 25-45 – are dying at an alarming rate because they think they are getting pharmaceutical-grade pills, or because they assume that what they’re buying online is as “safe” as pharmaceutical pills. They are dying because they are taking a lethal dose of fentanyl. They are dying because the heroin they bought has been laced with fentanyl.

While killing customers doesn’t make sense as a sustainable business model, drug traffickers don’t care if they lose some customers to death because of a deadly dose of fentanyl. The drug is so powerful and addictive, and the demand for opioids in the United States is so high, that new customers are always looking to buy more. The risks don’t matter when the addiction is so consuming.

In fact, fentanyl is so powerful that merely inhaling it, or simply touching it, can render a person unresponsive, especially if they have no or a low tolerance. A Gwinnett County officer, leaving a crime scene in which fentanyl was present (unknown to first responders), collapsed outside his police cruiser. Fortunately, another officer witnessed the incident and administered life-saving measures until he could be treated at a hospital. Somehow, fentanyl had entered his system at the scene.

“We insist that all fans and air conditioners be turned off, and that windows be closed before entering the scene where an overdose death is suspected,” said Johnson. “This drug is that deadly.” Common signs of a death being the result of an overdose include drugs on the scene, powder on surfaces, rolled dollar bills, syringes, and what one Medical Examiner’s Investigator Chad Johnson calls “fentanyl fade.” The “fade” refers to the position of the body, relaxed and slumped forward, the result of the central nervous system – and the body – shutting down.

Synthetic opioids (including fentanyl), are now the most common drugs involved in drug overdose deaths in the United States. In 2020, 57,000 opioid-related deaths involved fentanyl. As of May 2022, a staggering 75,000 Americans had died from fentanyl poisoning. The crisis is so prevalent that the Drug enforcement Authority (DEA) has constructed a special exhibit called “The Faces of Fentanyl,” a wall featuring photographs of victims of fentanyl poisoning.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, 107,375 people in the United States died of drug overdoses and drug poisonings in the 12-month period ending January 2022. Some of these deaths were attributed to fentanyl mixed with other illicit drugs like cocaine, methamphetamine, marijuana and heroin, with many users completely unaware they were also using fentanyl.

The real stories, however, lie not in statistics but in the human cost of substance abuse. Every death represents not only a victim of ravaging disease, but also that victim’s family and loved ones who have been devastated by struggle and loss.

The increased instance of the disease of addiction far outpaces this country’s capacity to effectively help these families. Shame, blame, incarceration and shunning of those who suffer from Substance Abuse Disorder have only made the problem worse, because the root causes and understanding of the condition are not yet fully understood or accepted. The government, judicial system, medical community and even churches are overwhelmed, trying to put out fires whose origins remain complex and misunderstood.

“When I was with the Atlanta Police department, the main drug we were seeing on the streets was Dilaudid,” said Tina Miller, Forensic Laboratory Manager and Investigative Consultant with the Gwinnett County Medical Examiner’s office. “We never see that any more.” In the 1980s, cocaine and crack cocaine were at the forefront of the illicit drug trade. With every passing decade, the drugs become more insidious, and the stakes are raised. Even so, fentanyl has added a new twist to substance abuse. With every use, any drug has the potential to kill.

I’ve been doing this for thirty years, and I’ve never seen anything like what we’re seeing now. ~ Dr. Carol Terry, Gwinnett County’s Chief Medical Examiner

Opioid settlement funding presents opportunities to address this epidemic

In addition to federal funding that Georgia receives each year to address Substance Abuse Disorder and mental health issues, the state will receive millions of dollars from recent opioid settlements with pharmaceutical companies and others involved in the distribution and sales of prescription opioids. Of course, Gwinnett County will receive a proportionate amount of the settlement funding.

Representatives from the Medical Examiner’s office and Navigate Recovery Gwinnett addressed Gwinnett’s Board of Commissioners at a Nov. 15 meeting, outlining the dire statistics concerning overdose deaths in the county, as well as proposed immediate and long-term solutions. The crippling cost of substance abuse, which has law enforcement, the fire department, the medical community, the justice system, treatment centers and other agencies groaning under the weight of it, is to be alleviated using these funds, according to the Georgia Budget and Policy Institute.

Substance abuse is directly related to theft, burglaries, homicides, sex crimes and many other crimes in the community. Everyone is affected.

“(The opioid abuse epidemic) is our fault. This is a man-made crisis,” said Barge. “We created a generation or two of people who are dependent on these drugs, and then we took them away. Now, we need to fix the problem.” Barge credits an accepting attitude toward the use of alcohol and marijuana with an entire generation’s need to chemically alter their moods.

He then went on to explain that in 2020, when COVID-19 hit, the problem was amplified. “People were told to isolate. They were cut off from support systems, family and friends. Many felt anxious, fearful and hopeless.” Not coincidentally, overdose deaths have increased significantly during and since 2020.

Barge suggested out-of-the-box thinking regarding immediate solutions, like making NARCAN® (naloxone) easily available to anyone, especially in areas known for high drug use and overdose deaths, via delivery methods similar to vending machines. North Carolina is already doing this, with positive results.

Using naloxone on someone who is unresponsive rapidly reverses an opioid overdose. There are times when it must be administered repeatedly in order to get the patient to the hospital for treatment, especially with the appearance of fentanyl and other dangerous additives in illicit drugs. Recently Xylazine, a large animal tranquilizer not approved for human use, is being added to illicit drugs, also with deadly results. Naloxone is so effective that first responders now have it with them at all times while on duty.

Naloxone is available, free, thanks to the Gwinnett, Newton, and Rockdale Health District, Georgia Overdose Prevention, and Navigate Recovery. Pharmacies also offer the lifesaving drug without a prescription, usually for a price. Starting in 2023, the Department of Behavioral Health will also have a supply of naloxone.

These opioid settlement dollars can be used to raise awareness and to treat overdoses. They can be used to provide naloxone to those who need it. That alone would cost millions of dollars. ~ Dr. Audrey Arona, Health Director for the Gwinnett, Newton and Rockdale County Health Departments

Amnesty Laws, also known as Good Samaritan Laws, provide amnesty to anyone who reports an overdose, even if they have drugs and paraphernalia in their possession. Lives can be saved if fear of arrest doesn’t prevent a person from reporting an overdose.

Dr. Audrey Arona, health director for the Gwinnett, Newton and Rockdale County Health Departments, also addressed Board members at the Nov. 15 Board of Commissioners meeting. “These opioid settlement dollars can be used to raise awareness and to treat overdoses. They can be used to provide naloxone to those who need it. That alone would cost millions of dollars.”

“I’ve been doing this for thirty years, and I’ve never seen anything like what we’re seeing now,” said Dr. Terry, addressing the commissioners.

Acutely aware of the need to immediately address overdose deaths, Dr. Terry agrees that providing free naloxone makes sense. She also said that, if a person is going to use illicit opioids anyway, they should be sure to use with a “buddy,” someone who can continually wake the user when they inevitably fall into a deep sleep from the effects of fentanyl and opioids. Ideally, the “buddy” would not be using drugs at the same time.

While none of these harm prevention measures is ideal, or even a viable long-term solution to a mushrooming epidemic, they do provide the immediate chance to prevent unnecessary deaths.

When communities of color are involved, treatment is punitive. In white communities, it is more about treatment. We don’t want to further disenfranchise communities of color. ~ Nicole Love Hendrickson, Chairwoman, Gwinnett County Board of Commissioners

Gwinnett community viewpoints

The Board of Commissioners, responsible for allocating the funding from opioid settlements, listened to the presentations made at the meeting, then asked questions of the presenters. Chairwoman Nicole Love Hendrickson said that the Board will soon be making decisions about how the settlement funds will be distributed. She noted that “When communities of color are involved, treatment is punitive. In white communities, it is more about treatment. We don’t want to further disenfranchise communities of color.”

Barge pointed out that fentanyl does not discriminate based on race, socio-economic class, education level, gender, or any other factors, and that there is a very real possibility of death even for a first-time, experimental user. He asked the Board of Commissioners to look at their budget and consider allocating funds to address the problem from several angles. Hendrickson stated that the Board would look at all solutions before making a decision.

No one has addiction as a life goal. No one wants to live like that ~ Foley Barge, Navigate Recovery

Is there any hope?

Barge is quick to stress that the message of addiction and recovery has to be one of hope, because hope is very real. An estimated nine percent of the population in the United States is living in recovery. In Gwinnett County, about 92,000 people are living successfully in recovery. “No one has addiction as a life goal. No one wants to live like that,” he said.

“Once we understand the science of addiction, and there is a science, we understand that the brain can heal,” Barge said. “It takes about eighteen to twenty-four months, but the brain can and does heal. People become themselves again. Their families get them back. They lead full, productive lives.”

“Don’t give up, and don’t give up on your loved one. Navigate Recovery is a great resource, and there are many others in our community. Help is out there. Education is critical, and prevention is the ultimate answer. We have to talk about this.” Shame, blame and denial only allow the epidemic to grow in the dark.

Barge is also quick to say that meeting with the Board of Commissioners was a step in the right direction. “We have to start talking about this. We have to educate people about what’s happening, how and why. That’s when we’ll find solutions. We can’t do anything if we don’t talk openly about this epidemic and this drug that is so deadly. We intended to try to inform and give perspective at that meeting, and I feel like we were able to do that.”

Editor’s Note: There are many elements of the opioid crisis that we are covering that affects our community, regardless of age, race, and ethnicity. If you or a loved one has been impacted by fentanyl in Gwinnett County, please contact us.